Energy considerations for training deep neural networks

environment machine learning nlp self-driving carsThe latest advances, both in hardware and theory of training neural networks, have enabled researchers to train very deep models on voluminous data (e.g. the Wikipedia corpus). The two main categories include networks that perform image recognition/classification and those that perform natural language processing tasks. Training such networks and achieving a high accuracy requires unusually large computational resources. As a result, these models are costly to train, fine-tune and deploy, both financially (due to the cost of purchasing hardware and paying electricity bills or renting cloud computing time) and environmentally, due to the carbon dioxide emissions required to run modern hardware.

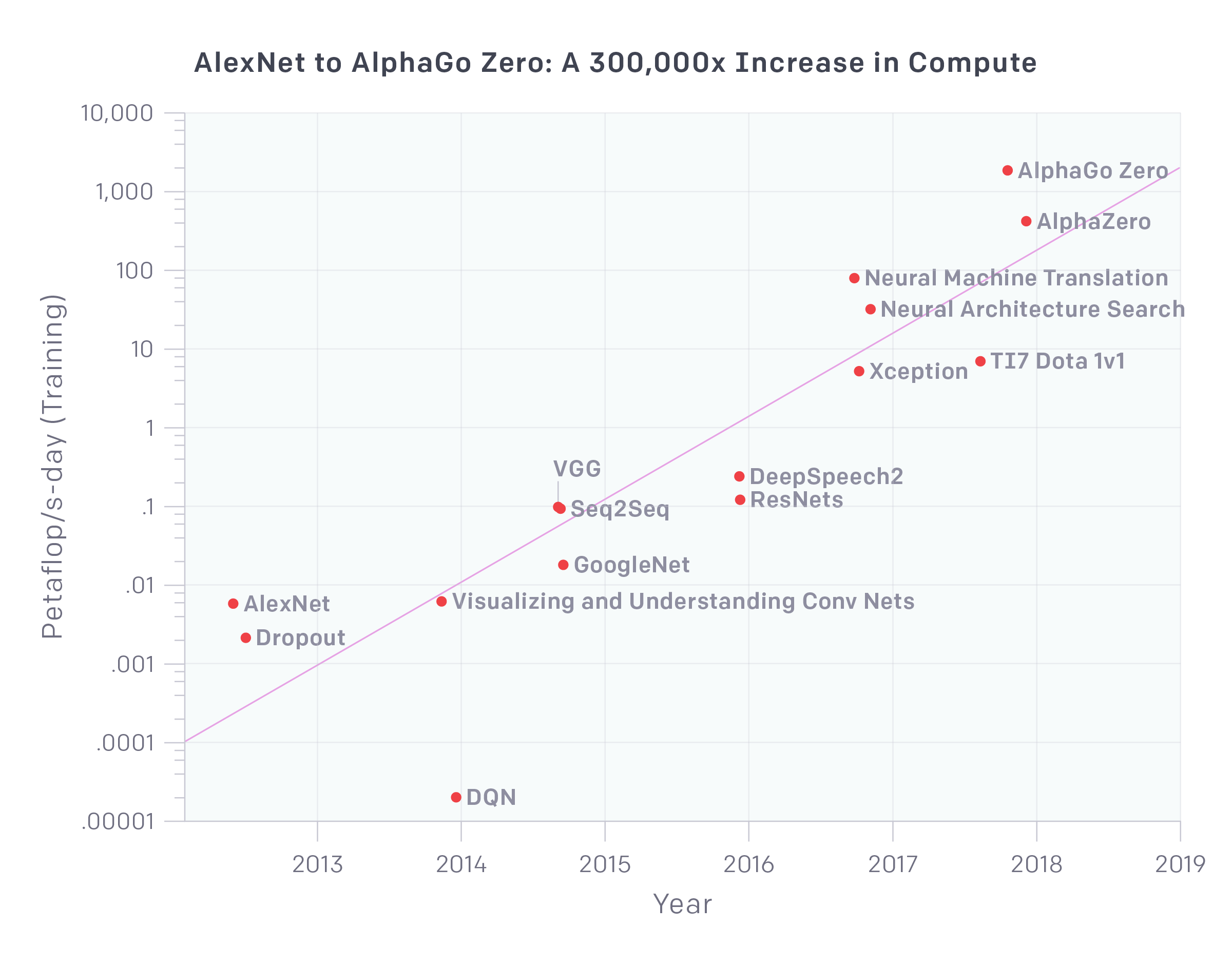

Image taken from here (mind that the vertical axis is in logarithmic scale, so what appears as a linear increase, in reality it’s an exponential growth).

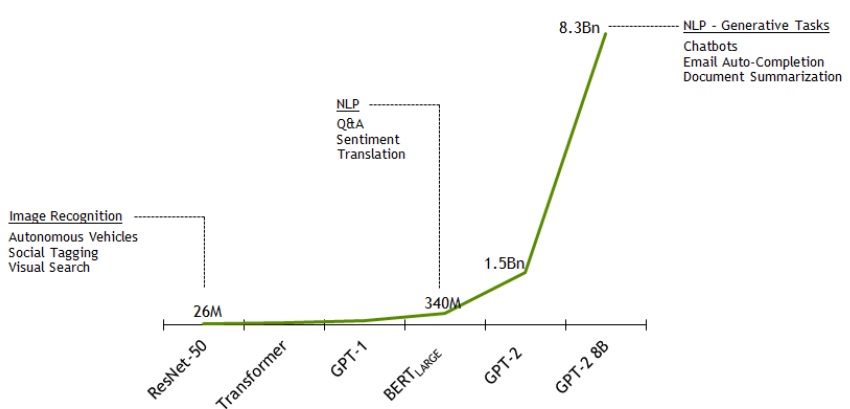

We will give a couple of examples on the depth of contemporary neural networks (DNNs). The BERT is a new language representation model which stands for “Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers” (Devlin et al, 2018). In its base form BERT has 110M parameters and its training on 16 TPU chips takes 4 days (96 hours). Another DNN from Radform et al (2019) has 1542M parameters, 48 layers and it needs 1 week (168 hours) to train on 32 TPUv3 chips. NVidia trained a 8.3 billion parameter version of a GPT-2 model known as GPT-2 8B.

Image taken from here.

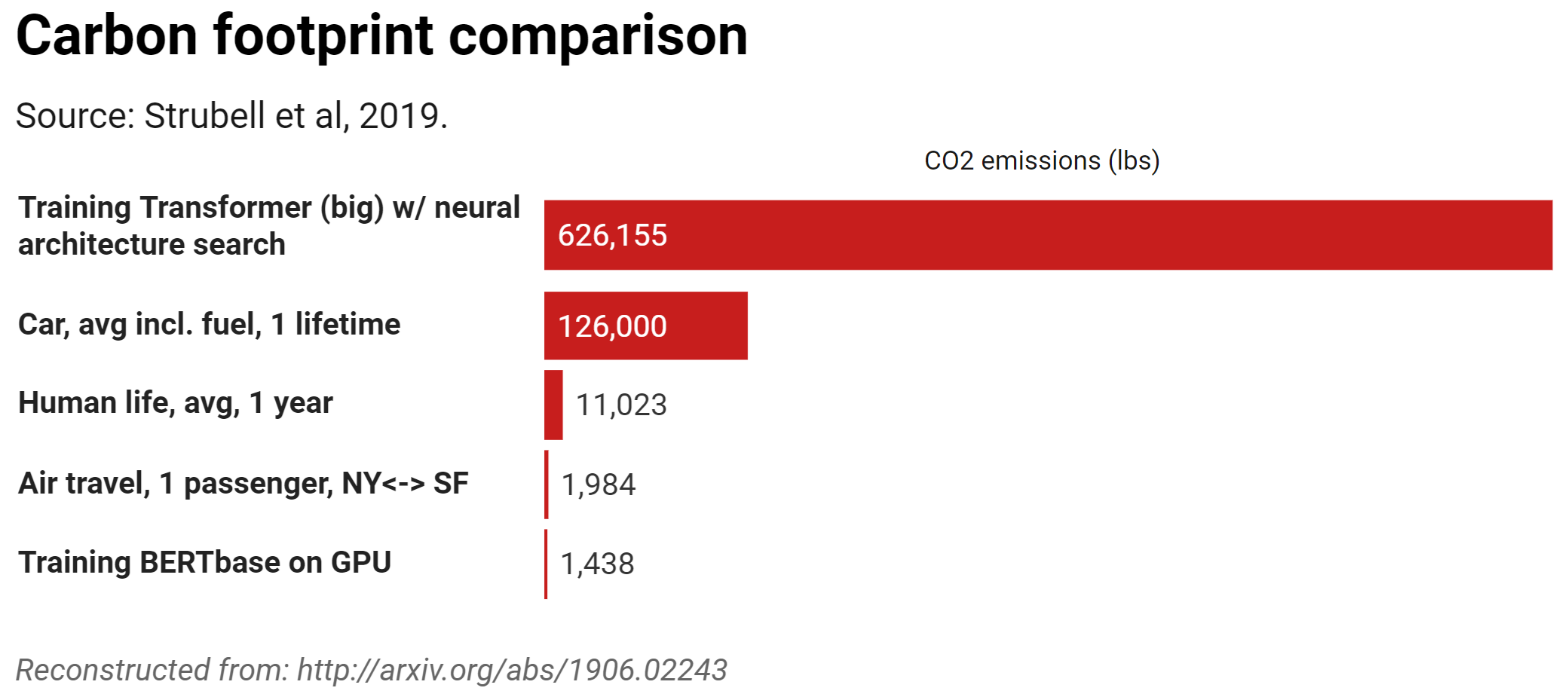

To put things in perspective, the carbon footprint of training BERT on GPU is comparable to that of a trans-American flight (Strubell et al, 2019)! But that’s nothing compared to the hyperparameter optimization of the “transformer big” model from So et al (2019), where an evaluation of 15K child models was performed, requiring a total of 979M train steps! This means that they trained 15K candidate models, with different learning parameters (i.e., parameters whose values the network cannot infer from the data and therefore they must be explicitly set by the researcher), to decide which one was the most promising to train it further.

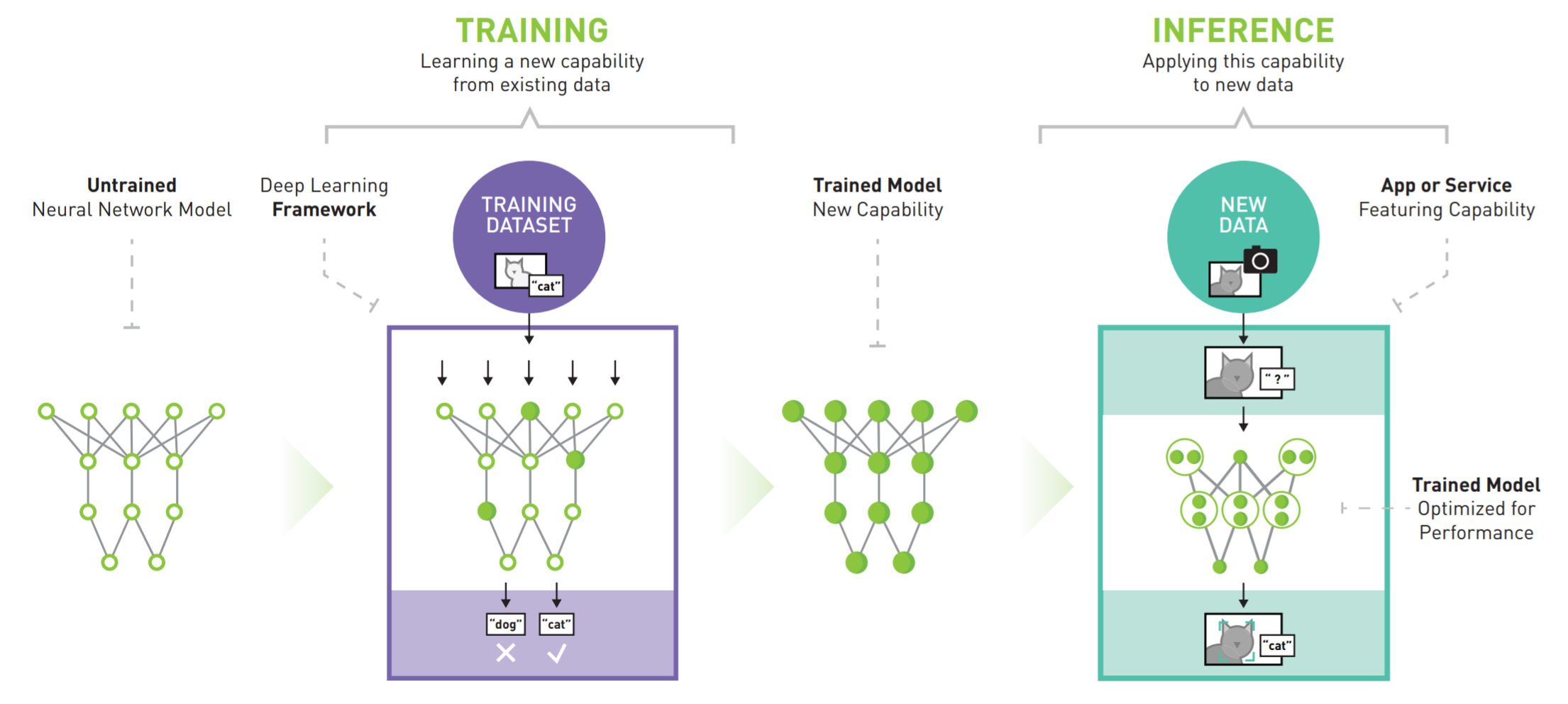

As mind blowing as these relative data are, the absolute environmental impact of training DNNs is small at the moment. The computational (hence environmental) cost of deploying the model for inference will surpass that of training (inference in this context means using your model in the real world, for the intended purpose, after you have trained it).

Image taken from a techical overview titled “NVIDIA AI Inference Platform”.

So, why will inference surpass the cost of training? Because you may train a network hundreds or thousands of times, but once you deploy it, it will be operating constantly multiplied by the number of your clients. For example, imagine a company that builds self-driving cars and after many iterations concludes on a DNN model that can safely navigate a car. This model is subsequently deployed to all cars and the network is continually fed with tons of real-time data (from cameras, radars, sensors, etc) that must process. Some estimates put the energy consumption of a self-driving car’s “neural brain” in the range 500 - 5000 watts!

Also, real-time applications may involve multiple inferences per instance. For example, a verbal question to an intelligent assistant like Siri may go through an automatic speech recognition, speech to text, natural language processing, a recommender system, text to speech and then speech synthesis. Each of these steps is a distinct inference operation on its own. These operations may be served over the cloud (when latency is not that much of an issue) or at client-side (when latency is an issue).

Things that might become important in the future for reducing the negative impact of AI deployment in the environment:

- Development of hardware that requires less energy and runs more efficiently on the AI training/inference workloads (e.g. dedicated chips for processing real-time data in self-driving cars).

- Development of efficient training algorithms or even better neural network architectures (with faster convergence, better generalization and requiring less math operations).

- Techniques to perform fast hyperparameter optimization (e.g. Bayesian search vs. grid/random search).

- Neural network compression techniques (for an overview this is an excellent introduction) for speeding up inference (some of them may be implemented at the harware level, e.g. check the advertised optimization features of NVIDIA TensorRT inference platform).

- Reduction of redundant training, perhaps through better tracking and sharing of training parameters (e.g. Weights & Biases product).

- Profiling tools to identify energy consumption offenders in an AI pipeline.

Fortunately, lots of computationally-oriented optimizations would also reduce (as a side effect) the environmental footprint. This is very important in my opinion, because it would be unrealistic to expect from industry to reduce CO2 emissions at the expense performance.

References

- Devlin J, Chang M-W, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding [Internet]. arXiv [cs.CL]. 2018. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805

- Radford A, Wu J, Child R, Luan D, Amodei D, Sutskever I. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog [Internet]. 2019;1(8). Available from: https://d4mucfpksywv.cloudfront.net/better-language-models/language_models_are_unsupervised_multitask_learners.pdf

- So DR, Liang C, Le QV. The Evolved Transformer [Internet]. arXiv [cs.LG]. 2019. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1901.11117

- Strubell E, Ganesh A, McCallum A. Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP [Internet]. arXiv [cs.CL]. 2019. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1906.02243